ASTORIA, Ore. — Residents of this small coastal city in the Pacific Northwest know what to do when there’s a tsunami warning: Flee to higher ground.

For those in or near Columbia Memorial, the city’s only hospital, there will soon be a different plan: Shelter in place. The hospital is building a new facility next door with an on-site tsunami shelter — an elevated refuge atop columns deeply anchored in the ground, where nearly 2,000 people can safely wait out a flood.

Oregon needs more shelters like the one that Columbia Memorial is building, emergency managers say. Hospitals in the region are likely to incur serious damage, if not ruin, and could take more than three years to fully recover in the event of a major earthquake and tsunami, according to a state report.

Columbia Memorial’s current facility is a single-story building, made of wood a half-century ago, that would likely collapse and sink into the ground or be swallowed by a landslide after a major earthquake or a tsunami, said Erik Thorsen, the hospital’s chief executive.

“It is just not built to survive either one of those natural disaster events,” Thorsen said.

At least 10 other hospitals along the Oregon coast are in danger as well. So Columbia Memorial leaders proposed building a hospital capable of withstanding an earthquake and landslide, with a tsunami shelter, instead of relocating the facility to higher ground. Residents and state officials supported the plans, and the federal government awarded a $14 million grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to help pay for the tsunami shelter.

The project broke ground in October 2024. Within six months, the Trump administration had canceled the grant program, known as Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, or BRIC, calling it “yet another example of a wasteful and ineffective FEMA program … more concerned with political agendas than helping Americans affected by natural disasters.”

Molly Wing, director of the expansion project, said losing the BRIC grant felt like “a punch to the gut.”

“We really didn’t see that coming,” she said.

This summer, Oregon and 19 other states sued to restore the FEMA grants. On Dec. 11, a judge ruled that the Trump administration had unlawfully ended the program without congressional approval.

The administration did not immediately indicate it would appeal the decision, but Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin said by email: “DHS has not terminated BRIC. Any suggestion to the contrary is a lie. The Biden Administration abandoned true mitigation and used BRIC as a green new deal slush fund. It’s unfortunate that an activist judge either didn’t understand that or didn’t care.” FEMA is a subdivision of DHS.

Columbia Memorial was one of the few hospitals slated to receive grants from the BRIC program, which had announced more than $4.5 billion for nearly 2,000 building projects since 2022.

Hospital leaders have decided to keep building — with uncertain funding — because they say waiting is too dangerous. With the Trump administration reversing course on BRIC, fewer communities will receive help from FEMA to reduce their disaster risk, even places where catastrophes are likely.

More than three centuries have passed since a major earthquake caused the Pacific Northwest’s coastline to drop several feet and unleashed a tsunami that crashed onto the land in January 1700, according to scientists who study the evolution of the Oregon coast.

The greatest danger is an underwater fault line known as the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which lies 70 to 100 miles off the coast, from Northern California to British Columbia.

The Cascadia zone can produce a megathrust earthquake, with a magnitude of 9 or higher — the type capable of triggering a catastrophic tsunami — every 500 years, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Scientists predict a 10% to 15% chance of such an earthquake along the fault zone in the next 50 years.

“We can’t wait any longer,” Thorsen said. “The risk is high.”

Building for the Future

The BRIC program started in 2020, during the first Trump administration, to provide communities and institutions with funding and technical assistance to fortify their structures against natural disasters.

Joel Scata, a senior attorney with the environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council, said the program helped communities better prepare so they could reduce the cost of rebuilding after a flood, tornado, wildfire, or extreme weather event.

To qualify for a grant, a hospital had to show that the project’s benefits were greater than the future danger and cost. In some cases, that benefit might not be readily apparent.

“It prevents bad disasters from happening, and so you don’t necessarily see it in action,” Scata said.

Scata noted that the Trump administration has also stopped awarding grants through FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, which predates BRIC.

“There really is no money going out the door from the federal government to help communities reduce their disaster risk,” he said.

A recent KFF Health News investigation using proprietary data from Fathom, a global leader in flood modeling, found that at least 170 U.S. hospitals are at risk of significant and potentially dangerous flooding from more intense and frequent storms. That count did not include Columbia Memorial, as Fathom’s data did not account for tsunamis. It models flooding from rivers, sea level rise, and extreme rainfall.

In recent days, an atmospheric river — a narrow storm band carrying significant amounts of moisture — dumped more than 15 inches of rain on parts of Oregon and Washington, causing catastrophic flooding along rivers and the coast. In the Washington town of Sedro-Woolley, which sits along the Skagit River, the PeaceHealth United General Medical Center evacuated nonemergency patients.

High winds battered Astoria, leaving the city with some minor landslides, according to news reports. But flooding on the road to the nearby beach town of Seaside made the drive nearly impassable.

The Trump administration is leaning on states to take greater responsibility for recovering from natural disasters, Scata said, but most states are not financially prepared to do so.

“The disasters are just going to keep on piling up,” he said, “and the federal government’s going to have to keep stepping in.”

A Hospital at Risk

Columbia Memorial is blocks from the southern shore of the Columbia River, near the Washington border, where the area’s natural hazards include earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and floods. A critical access hospital with 25 beds, it opened in 1977 — before state building codes addressed tsunami protections.

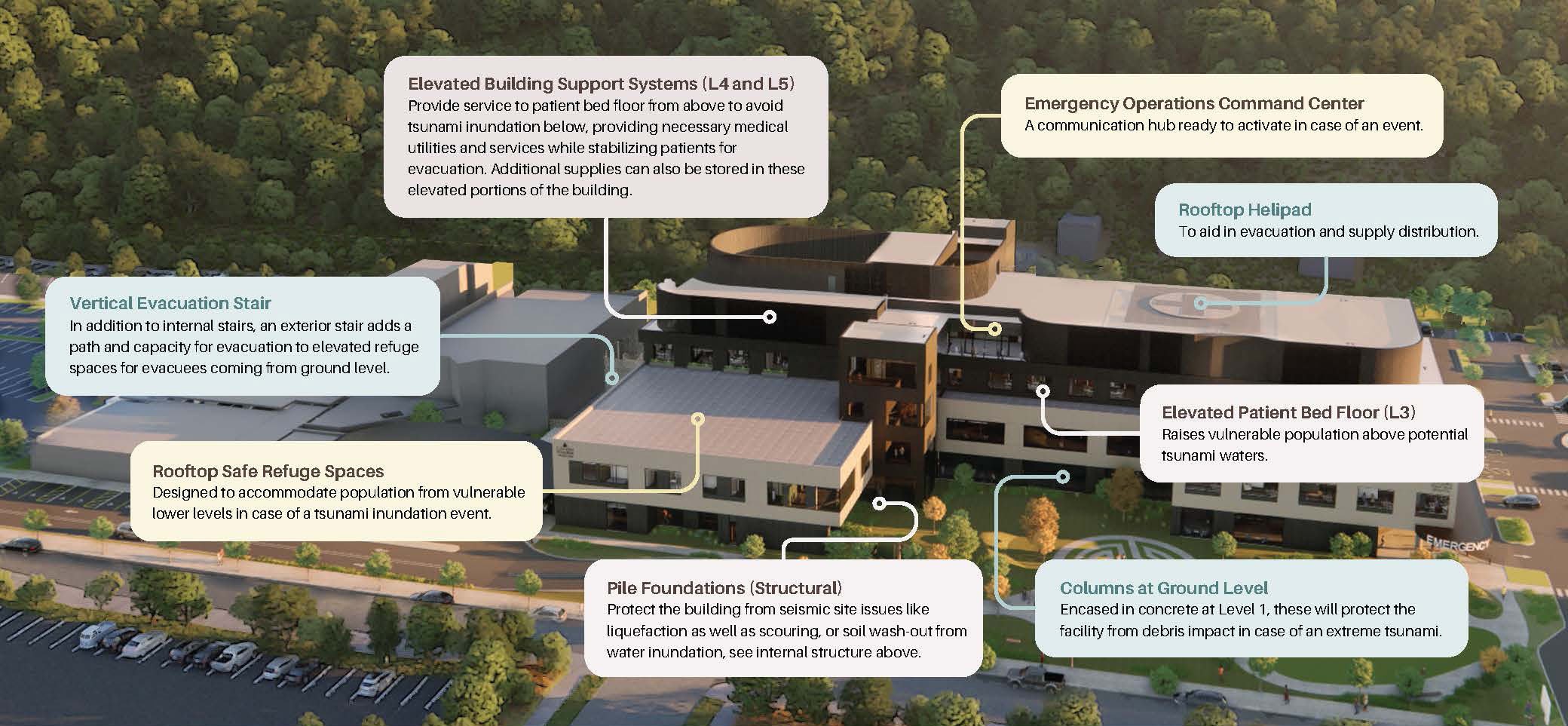

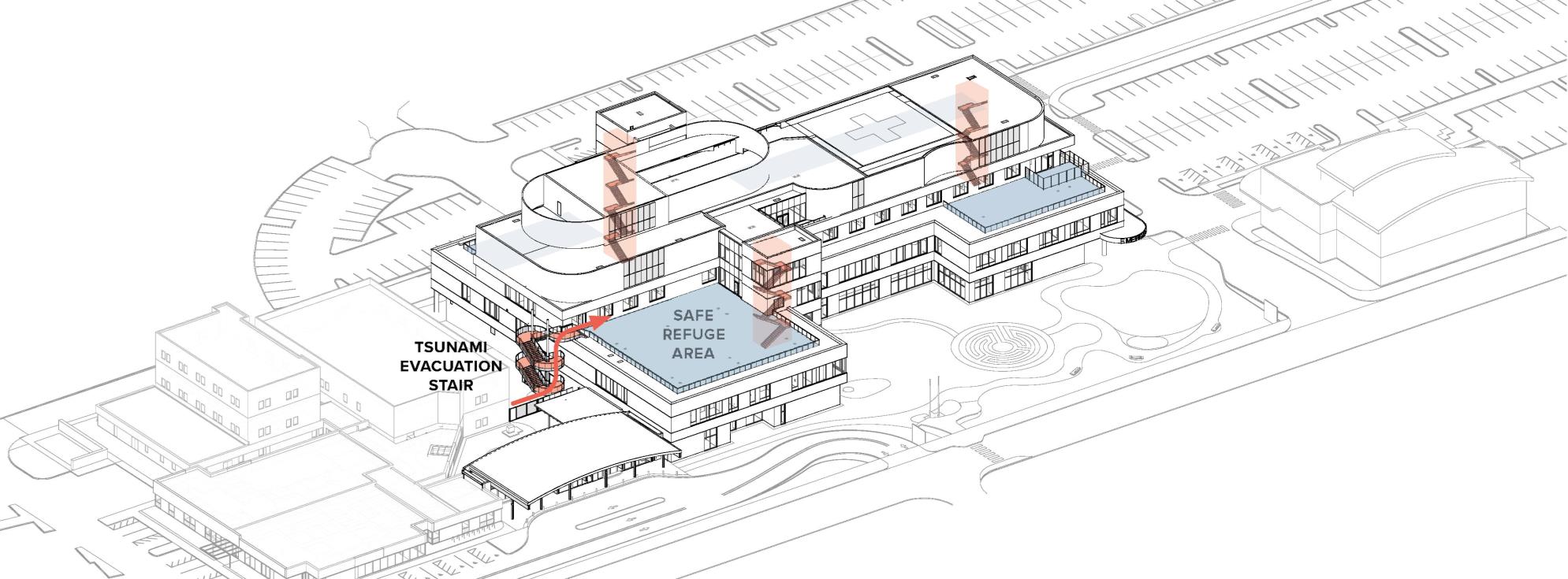

Thorsen said the new facility and shelter would be a “model design” for other hospitals. Design plans show a five-level hospital built atop a foundation anchored to the bedrock and surrounded by concrete columns to shield it from tsunami debris.

The shelter will be on the roof of the second floor, above the projected maximum tsunami inundation. It will be accessible via an outdoor staircase and interior staircases and elevators, with enough room for up to 1,900 people, plus food, water, tents, and other supplies to sustain them for five days.

With most patient care provided on the second and third levels, generators on the fourth level, and utility lines underground, the hospital is expected to remain operational after a natural disaster.

Thorsen said an earthquake and tsunami threaten not only vast flooding but also liquefaction, in which the ground loosens and causes structures above it to collapse. Deep foundations, thick slabs, and other structural supports are expected to protect the new hospital and tsunami structure against such failure.

Through the years, hospital administrators and civic leaders in Astoria have sought other locations for Columbia Memorial. But relocation wasn’t economical. Columbia Memorial committed to invest in a new hospital and tsunami shelter to protect not only patients and staff but also nearby residents.

“Your community should count on your hospital to be a safe haven in a natural disaster,” Thorsen said.

Fighting To Restore Funds

The estimated construction budget for Columbia Memorial’s expansion is $300 million, mostly financed through new debt from the hospital. The tsunami shelter is budgeted at about $20 million, for which FEMA’s BRIC program awarded nearly $14 million, with a $6 million matching grant from the state, which has maintained its support.

The shelter and the building’s structural protections — featuring reinforced steel, deeper foundations, and thicker slabs — are integral to the design and cannot be removed without compromising the rest of the structure, said Michelle Checkis, the project architect.

“We can’t pull the TVERS [tsunami vertical evacuation refuge structure] out without pulling the hospital back apart again,” she said. “It’s kind of like, if I was going to stack it up with Legos, I would have to take all those Legos apart and stack it up completely differently.”

Columbia Memorial has sought help from Oregon’s congressional delegation. In a letter to Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and former FEMA acting administrator David Richardson, the lawmakers demanded that the agencies restore the hospital’s grant.

The hospital’s leadership is seeking other grants and philanthropic donations to make up for the loss. As a last resort, Thorsen said, the board will consider removing “nonessential features” from the building, though he added that there is little fat to trim from the project.

The lawsuit brought by states in July alleged that FEMA lacks the authority to cancel the BRIC program or redirect its funding for other purposes.

The states argued that canceling the program ran counter to Congress’ intent and undermined projects underway.

In their response to the lawsuit, the Trump administration said repeatedly that the defendants “deny that the BRIC program has been terminated.”

The lawsuit cites examples of projects at risk in each state due to FEMA’s termination of the grants. Oregon’s first example is Columbia Memorial’s tsunami shelter. “Neither the County nor the State can afford to resume the project without federal funding,” the lawsuit states.

In response to questions about the impact of canceling the grant on Astoria and the surrounding community, DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin said BRIC had “deviated from its statutory intent.”

“BRIC was more focused on climate change initiatives like bicycle lanes, shaded bus stops, and planting trees, rather than disaster relief or mitigation,” McLaughlin said. DHS and FEMA provided no further comment about BRIC or the Astoria hospital.

Preparing for a Tsunami Disaster

Located near the end of the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail, Astoria sits on a peninsula that juts into the Columbia River near the Pacific Ocean.

Much of the city is not in the tsunami inundation area. But Astoria’s downtown commercial district — where gift shops, hotels, and seafood restaurants line the streets — is nearly all an evacuation zone.

Two hospitals — Ocean Beach Health in nearby Washington, and Providence Seaside Hospital in Oregon — are about 20 miles from Columbia Memorial. Both are 25-bed hospitals, and neither is designed to withstand a tsunami.

Ocean Beach Health regularly conducts drills for mass-casualty and natural disasters, said Brenda Sharkey, its chief nursing officer.

“We focus our planning and investments on areas where we can make a real difference for our community before, during, and after an event — such as maintaining continuity of care, ensuring rapid triage, and coordinating with regional emergency partners,” Sharkey said in an email.

Gary Walker, a spokesperson for Providence Seaside, said in a statement that the hospital has a “comprehensive emergency plan for earthquakes and tsunamis, including alternative sites and mobile resources.”

Walker added that Providence Seaside has hired “a team of consultants and experts to conduct a conceptual resilience study” that would evaluate the hospital’s vulnerabilities and recommend ways to address them.

Oregon’s emergency managers advise residents and visitors in coastal communities to immediately seek higher ground after a major earthquake — and not to rely on tsunami sirens, social media, or most technology.

“There may not even be cellphone towers operating after an event like this,” said Jonathan Allan, a coastal geomorphologist with the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries. “The earthquake shaking, its intensity, and particularly the length of time in which the shaking persists, is the warning message.”

The stronger the earthquake and the longer the shaking, he said, the more likely a tsunami will head to shore.

A tsunami triggered by a Cascadia zone earthquake could strike land in less than 30 minutes, according to state estimates.

Many of Oregon’s seaside communities are near high-enough ground to seek safety from a tsunami in a relatively short time, Allan said. But he estimated that, to save lives, Oregon would need about a dozen vertical tsunami evacuation shelters along the coast, including in seaside towns that attract tourists and where the nearest high ground is a mile or more away.

Willis Van Dusen’s family has lived in Astoria since the mid-19th century. A former mayor of Astoria, Van Dusen stressed that tsunamis are not a hypothetical danger. He recalled seeing one in Seaside in 1964. The wave was only about 18 inches high, he said, but it flooded a road and destroyed a bridge and some homes. The memory has stayed with him.

“It’s not like … ‘Oh, that’ll never happen,’” he said. “We have to be prepared for it.”

KFF Health News correspondent Brett Kelman contributed to this report.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).